2023 Global Top 50 law firm brands + a decade of change

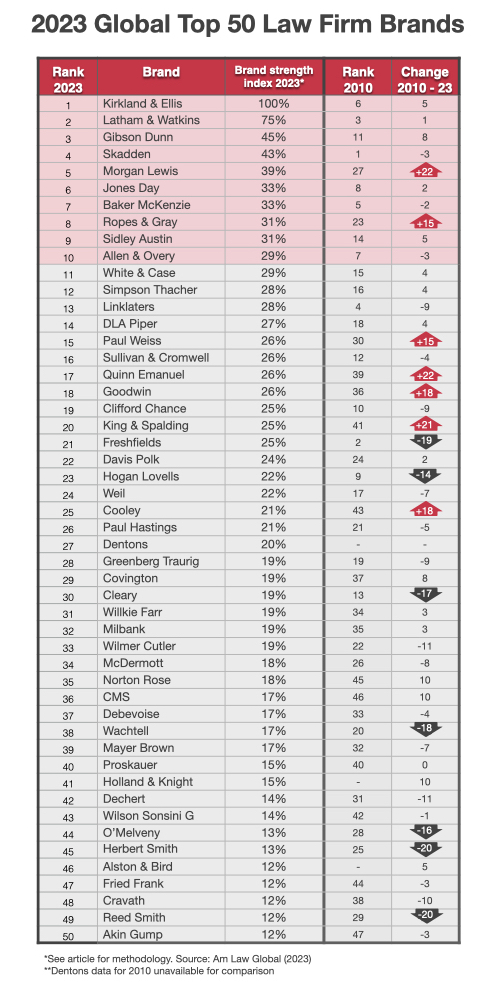

Principia’s 2023 Global Top 50 Law Firm Brand Index focuses on the changes in brand rankings over the last decade and today’s snapshot. This perspective highlights some pretty seismic changes – some big risers and some big fallers – that aren’t as easy to spot in year-on-year data.

Highlights

- US-headquartered firms now dominate the top 10 global rankings.

- UK-headquartered firms have failed to keep pace with their US-headquartered peers.

- The strongest brands are accelerating away from the rest.

- Several firms have transformed their brand strength relative to peers over the last decade.

- A similar number of firms have declined rapidly relative to peers over the past decade.

(See the end of the article for details of our methodology and an explanation of the direct correlation between brand strength and overall profitability).

(See the end of the article for details of our methodology and an explanation of the direct correlation between brand strength and overall profitability).

Kirkland & Ellis retains its dominance as the strongest Big Law firm brand and increasingly looks unassailable in its no.1 positioning.

New world order

The headline story is the top ten takeover by a group of super-profitable US-headquartered and increasingly global firms displacing the UK-headquartered global firms. In 2010, four of the top ten firms called London home, whereas today, only one UK-headquartered firm retains a top ten ranking (Allen & Overy at number ten).

To some extent, the new global top ten firms are boosted by the relative size and strength of the US market. But that doesn’t tell the whole story; the US market was just as big and lucrative in 2010. The story of the last decade is that these US-headquartered firms have made strategic moves to rapidly internationalise their brands, particularly in London, which has benefitted them and made life much more challenging for the London incumbents.

At the same time, the elite UK firms have re-doubled their strategic focus on the US market but have not yet made the same inroads as those firms coming the other way. A&O’s recent merger announcement with Shearman & Sterling could signal the start of a fightback.

Since 2010, the most prominent firms have accelerated away from the pack.

The long view

Our decade-long perspective shows that, whilst year-to-year changes in brand rankings are primarily subtle, taking a longer view shines a light on some pretty dramatic changes.

Unsurprisingly, the strongest Big Law firm brands are becoming relatively more robust than their close but not quite close enough competitors. It happened decades ago in all other professional services sectors where a dominant Big 4/5/6 emerged that got ahead and stayed ahead.

For a while, the Big Law market seemed to defy gravity in this sense. However, since 2010, the most prominent firms have accelerated away from the pack.

Some firms have outperformed their peers in brand strength to the point where – if it were sport – they would have been promoted to a higher league. Similarly, some firms would have been demoted by now.

The headline story is the top ten takeover by a group of super-profitable US-headquartered firms displacing the UK-headquartered global firms.

Upwardly mobile

Kirkland & Ellis retains its dominance as the strongest Big Law firm brand and increasingly looks unassailable in its no.1 positioning. However, it’s worth remembering that the firm was ‘only’ ranked 4th in 2010. It’s not had success handed to it on a plate.

Latham, Gibson, and Skadden continue to maintain their rankings. Although Skadden has let the others catch up since 2010, when it was ranked no.1. It’s important to note that whilst these firms have been in the top 5 of law firm brands for some years now, they continue to build brand strength even faster than their followers.

Morgan Lewis and Ropes & Gray have had an incredible brand-strength decade, leaping into the top 10 from ranking 27 and 23, respectively. Since firms might only move a place or three in any year, their success shows how incremental improvements year-on-year can have a transformational impact.

Outside of the top 10, Paul Weiss, Quinn Emanuel, Goodwin, King & Spalding, and Cooley have each leaped up more than 15 places in the top 50 rankings since 2010.

Again, consistent improvement in brand equity over a decade has taken these three firms from being ranked in the bottom half of the top 50 to firmly established in the top 25 most valuable brands.

Freshfields has suffered along with the rest of the Magic Circle – only more so.

Losing ground

The biggest Top 50 fallers since 2010 are Freshfields, Hogan Lovells, Cleary, Wachtell, O’Melveny, Herbert Smith and Reed Smith.

Each of these firms has a different story behind their relative decline in the rankings:

Freshfields has suffered along with the rest of the Magic Circle – only more so. Hogan Lovells has been busy bedding down its merger. Cleary has lost its distinctiveness as an elite transatlantic firm and has not yet found a new brand strategy. O’Melveny (like Shearman) is in long-term decline and needs to find a new strategy or a merger quickly. Like the Magic Circle, Herbert Smith suffers from the influx of US firms in London. Reed Smith isn’t managing to retain premium credentials.

Wachtell is another story entirely. The firm continues to dominate PEP rankings whilst eschewing expansion.

Nice problem to have, you might say, if you’re a current partner. But what about the long-term future of the brand? Is their strategy to be the IB equivalent of a Lazard or Rothchild in a world dominated by firms like Goldman Sachs?

Or, taking an even longer view, do they want to be Maserati or Mercedes?

Interestingly, inside each of these firms, things probably feel fine. PEP has risen since 2010. Only just in some cases, but it hasn’t fallen off a cliff.

But this analysis shows that whilst they’ve been treading water, their peers have moved much faster – either by growing their brand premium, expanding their brand reach, or both.

Brand is not about logos; brand is a strategy made visible.

Roaring Twenties?

Looking ahead, will this be the decade where a global elite of Big Law firms finally emerges, leaving an unbridgeable chasm behind them?

Law differs from accounting and consulting regarding conflicts and the number of different roles in many deals and disputes. And what’s the magic number of global elite firms that the market will settle down on? Ten, fifteen, twenty?

How different? Only time will tell. And unlike these other sectors, there are likely to be significant niche strategies and brand positionings that firms can exploit if they find themselves on the wrong side of the chasm.

—

Methodology and economics sidebar – why total partnership profits are a good measure of relative brand strength in Big Law.

Brand is not about logos; brand is a strategy made visible. A stronger brand gives a law firm better leverage in the competition for high-value work and more ability to maintain premium pricing (i.e. avoid discounts when it does land the work), which translates into higher profitability.

The systematic publication of detailed performance data in the Big Law sector makes it uniquely possible to analyse and rank the relative brand strengths of the largest firms robustly and consistently, effectively tracking actual client behaviours, not simply canvassing their opinions.

The basis of our measurement of a firm’s brand strength is its ‘perceived brand premium’ – the premium its clients are prepared to pay to engage the firm (measured by PEP) multiplied by its ‘perceived brand reach’ – how far the firm can extend this premium without dilution (measured by number of equity partners).

The efficacy of our methodology lies in the underlying dynamics of the global law firm market, which, although quirky in many ways, is, in economic-theory terms, a reasonably frictionless or ‘pure’ market (lots of competitors with relatively low market share, low barriers to entry/exit, similar products, and excellent price visibility).

In other sectors, profits can be heavily influenced by ownership of critical IP (pharma), regulations and licences that thwart competition (telecoms), assets that bar entry (energy), effective monopolies or oligopolies (big tech), etc., none of which applies in any significant way in the premium legal market.

Firms only succeed if they compete effectively year in and year out for what they earn. And because the purchase cycle is relatively short, clients can react quickly to any perceived changes in the relative competitiveness of any one firm.

Being a relatively ‘pure’ market, individual firms (and their partners) compete based on three components: reputation (what those who’ve experienced you think about your service), relevance (what problems you’re perceived to be best at solving and where geographically you solve them) and visibility (how well known you’re known to the clients around the world who have those problems – and the budgets to pay for your services).

These three components comprise a firm’s ‘brand’ – the combined brand equity of the firm and its partners (who also have brands of their own) – arguably the only source of sustainable competitive advantage that a law firm has. And, any serious attempt to improve a firm’s overall performance by enhancing its brand reputation must rigorously engage with these issues; if not, it risks just being decoration.

It’s important to note that being a ‘stronger’ and more valuable brand overall does not necessarily imply being a ‘better’ brand for every occasion. For instance, the Mercedes brand is regularly measured to be about ten times as valuable as the Ferrari brand ($50bn vs $6bn), but that doesn’t mean that Ferrari isn’t a strong brand in its niche. It’s just not as valuable overall because, relative to Mercedes, its niche is tiny.